Drawing naked men and jetting around the world: Who says you're past it at 92?

By Diana Athill

Last week, I signed up to a new life-drawing class. Nothing amazing about that, you might think - but I am 92, so each new experience is a blessing. Of course, I was the oldest person there, but it was lovely.

We had a splendid model, an African dancer about 70 years my junior. He was absolutely beautiful, and a good model, too - great at holding his poses. You'll be pleased to know we had two little electric fires to keep him warm.

We had a splendid model, an African dancer about 70 years my junior. He was absolutely beautiful, and a good model, too - great at holding his poses. You'll be pleased to know we had two little electric fires to keep him warm. Diana Athill, 92, is determined not

to let her age hold her back

I'm telling you this story because on my way to the first class, I took a little tumble. I was hurrying along the pavement and stupidly stubbed my toe and fell down. Within minutes, a young woman driver had stopped to help and gently got me to my feet. Soon, I was on my way again. That evening encapsulated two of the good things about old age.

First, it has been a great bonus to discover new pursuits. Ordinary things have become more valuable because I am old, enjoyed with increasing intensity because of the knowledge that I shan't be able to enjoy them for much longer.

Second, it has been a lovely surprise to receive unexpected kindnesses nearly every day.

People rush to help me with my shopping, for instance, and young people are almost universally sweet and kind.

I've been surprised by how much I enjoy being old - but I've been lucky.

I've been surprised by how much I enjoy being old - but I've been lucky. There are too many old people who have a wretched time, and sometimes the British treat their old worse than they treat animals. Certainly, the elderly are too often left to rot, and I wish the Government would devote more money to their care. Silly old Martin Amis didn't help by saying we should introduce euthanasia booths, in which the elderly would be dispatched with a martini and a medal, but we do have to face the problem of an ageing population. This got me thinking: what is it that makes a good old age? Much has been written about being young, but there is not much on record about falling away. So I shall address the subject.

Having a good old age comes down to luck

First, I have to tell you a good old age largely comes down to luck. If you're ill, it's ghastly. And if you have no money, or a mind never sharpened by good education or absorbing work, or a childhood warped by cruel parents, then anything said about old age by a luckier person is likely to be meaningless, or even offensive. But if you keep your wits and health about you, I'm pleased to report that it is OK.

I continued working as a literary editor, publishing some of the most important novelists of the 20th century, until I was 75: one does eventually go off the boil, but you shouldn't take the pan off the hob too early. I could have gone on until I was gaga if I wanted to, but I recognised that you do become a bit less sharp eventually.

After retiring, I began writing. By the time I was 80 I had written one book, and now I have written two more. That has elevated me into the class of old person about whom people say: 'Isn't she wonderful?'

Sometimes it's patronising, but usually it is meant well. One of the lovely things about old age is that you are praised for doing so little. As Alan Bennett wrote in his diary: 'Once you're over 80, you only have to eat a soft-boiled egg and everyone thinks you're marvellous.'

But even if you have your health, attitude is all-important.

As you get older, you come up against a tiredness. You wake up in the morning and you don't really feel like getting up, but it's important to make yourself do it. You should never utter the words: 'I am too old for that.

As you get older, you come up against a tiredness. You wake up in the morning and you don't really feel like getting up, but it's important to make yourself do it. You should never utter the words: 'I am too old for that.' For many years, I had a friend who had a hopeless outlook. I would say to her: 'You must replace your fridge,' and she would reply:

'I don't think it is worth it at our age.'

She collapsed, poor darling, and died some time ago. My good friend Jean Rhys, the novelist, was also one of my object lessons, demonstrating how not to think about getting old. She expected old age to make her miserable - and so, of course, it did.

Diana has been having fun with friends at a life drawing class

For my part, I waste no time worrying about death. I am more concerned with the experience of living during one's last years. What is old age like physically? You become more limited, but essentially I don't feel any different now. The only thing I mind horribly is that I am very deaf. There are things I used to like doing that I don't now - like sex. This was not a sudden event, its early stages occurred in my late 50s. I was forced into acceptance of this when our household was invaded by a ruthless and remarkably succulent blonde lodger in her mid-20s, and my partner Barry fell into bed with her.

There was one sleepless night of real sorrow, but only one night.

What I mourned was not the loss of my loving old friend Barry, who was still there, but the loss of youth.

'What she has, God rot her, I no longer have and will never, never have again.'

Later came another milestone along the path of old age - accepting that I should move into an old person's home.

Rationally, I knew it was a good idea - in your 90s, things such as cooking and bill become more difficult. It was hard closing down my old life in order to go into a home. I had a flat I had lived in for 50 years. When it came to getting rid of my 2,000 books, it was quite awful - painful beyond belief. The move has brought me great happiness, however. When I arrived at the home before Christmas, I was shown into a delightful bed-sitting room, and from that moment I have been very happy here and have made friends. I intend to make more.

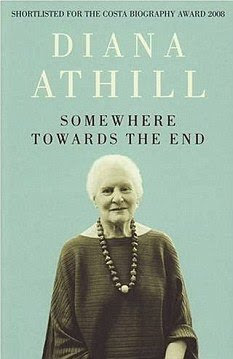

Diana is also a published author, with her biography Somewhere Towards the End shortlisted for the Costa Biography Award 2008

I found out about the place from a friend, who had to move in here. I thought: 'The poor old dear,' and went to visit her. She said: 'Darling, you've got to come and live here, it is wonderful - they do everything for you.' I said: 'Isn't there an enormous waiting list?' And she said: 'Oh no dear, we're dying all the time.' There are hoots of laughter here when I tell that story. I rise at 8am, have a shower, breakfast on toast and honey, and perhaps yoghurt and fruit. Then I potter about in the car, posting letters, going to the bank, visiting friends and shopping. It's one long holiday, you see, although I am working on my next book. It is important not to collapse because everything is done for you - you have to keep your life going and your mind lively. Last October, I was asked to go to a literary festival in Canada. I had been rather ill, and declined - then I realised that was the wrong attitude. One must always try to overcome feebleness if one feels feebleness coming on. I went, and would not have missed a moment of it. I got to see Niagara Falls and shared a stage with the author Alice Munro. We were given a standing ovation. She wrote to me: 'Do you think it's too late for us to travel as a double act?'

Money and health is one thing, but the luckiest elderly people of all are those who have something in their own heads that they want to do, such as writing or painting. That is a gift. If you don't have that gift, you must look for it and find something that interests you.

The most important thing of all is to fight depression. Of course, it can be miserable, with your friends dying and health failing. Moving through advanced old age is a downward journey. But you have to look for the good things. I always think of the Jewish concert pianist Alice Herz-Sommer, who is 107. She endured the miseries of the Prague ghettos and was sent to Theresienstadt concentration camp, where nearly 35,000 prisoners perished. Her husband was moved to Auschwitz in 1944. She never saw him again. Yet, she is the most optimistic person you could come across. She still plays the piano for three hours a day.

In a recent interview, she said: 'It isn't that I don't know about the bad, but I think about the good.' If I ever feel a little down, I think of her. I know about the bad, but I think about the good - that life is beautiful. Because, in so many ways, it is.

[rc]

© Associated Newspapers Ltd