Experts struggle to find ways to spot condition earlier>

Experts struggle to find ways to spot condition earlier>Illustrations Courtesy:

mothersover40.com

WASHINGTON (Associated Press), December 10, 2007:

Wake up to find your shoulder killing you but don't recall an injury? It could be the start of frozen shoulder, a curse of middle-aged women and one of the most puzzling joint conditions.

The shoulder's normally smooth lining becomes so inflamed it resembles cherry Jell-O. That leads to scar tissue, making the shoulder too stiff to move.

Known medically as adhesive capsulitis, it's a fairly common ailment — estimated to strike between 2 percent and 3 percent of the population, the vast majority women ages 40 to 60. Yet too few sufferers get diagnosed in time for a simple shot that could cut an astounding year or more off recovery time.

In fact, doctors can easily confuse early symptoms with a rotator cuff injury — and the wrong physical therapy can worsen a frozen shoulder-in-progress by further irritating it.

So Dr. Jo Hannafin of New York's Hospital for Special Surgery is excited when patients show up after only two to three months of shoulder pain. She injects cortisone deep into the joint and 15 minutes later lifts and twists it.

"If the range of motion is now full, I've hit a home run," says Hannafin, a leading expert on the condition. "I've caught a patient in the first stage."

That early treatment means they'll be healed in about a month. "This is going to be gone."

But usually patients show up months later. Wait too long, and recovery can take two years or more.

"You must be a patient patient," says Dr. Gregory Nicholson, a shoulder specialist at Chicago's Rush University Medical Center. "I tell my patients they got roped into the most stubborn and misunderstood condition. Sometimes it just wears you down."

Why the mystery? Nobody knows just what triggers frozen shoulder. It seems to strike out of the blue.

Diabetics are at higher risk; up to 20 percent get it. Having an underactive thyroid also is a risk factor. Trauma sometimes precedes a frozen shoulder.

Diabetics are at higher risk; up to 20 percent get it. Having an underactive thyroid also is a risk factor. Trauma sometimes precedes a frozen shoulder. Add the fact that 70 percent of patients are middle-aged women, and specialists say hormones clearly play some role but they don't know what.

Beyond that, it's hard to predict who will get adhesive capsulitis, or how severe a case. It doesn't strike the same shoulder twice, but at least 15 percent of patients eventually suffer a bout in the opposite shoulder.

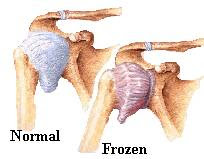

Surrounding the ball of the shoulder is a thin stretchy sac, or capsule. Inflammation in that lining is the start of frozen shoulder, and it causes immense pain.

When the pain starts to wane, that's bad news. It means the capsule is thickening with excess collagen, a sort of scar tissue, that further stiffens the shoulder. Eventually, the body can mostly recover on its own. But it takes so long that most late-stage patients find themselves undergoing painful physical therapy or even surgery to break apart the collagen and spur thawing.

Only in recent years have studies proven that a cortisone injection in the earliest stages can prevent collagen buildup and spur dramatically faster recovery, sometimes in mere months.

Now the challenge is to get more sufferers treated early. Key signs: Pain at night and at rest, along with gradually increasing stiffness. Movement problems typically begin with reaching back and up, like into a back pocket or to unfasten a bra. An exam should include the doctor attempting to lift and rotate the arm; problems with this so-called passive movement are another tipoff.

Rush's Nicholson says it's not uncommon for patients to seek him out after initially being told they had another shoulder injury and unknowingly aggravating their frozen shoulder with too-aggressive physical therapy. It takes gentle stretching to supplement the cortisone, he cautions.

"The biggest problem is the patients who ... just didn't know they were supposed to see a doctor," Dr. Beth Shubin Stein of the Hospital for Special Surgery told a recent seminar by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. "Now they're out of that window where they're treatable with that steroid."

A New York drug company is funding research to tell if injecting another substance — a collagen-digesting enzyme called collagenase — might someday help those later-stage patients, but it's too soon to tell.

Debbie Karlitz knows the frustration: She's had the condition in each shoulder.

A cortisone injection and physical therapy brought relief in a few months to the first shoulder. But Karlitz's second bout has lasted over a year. Pain wakes her at night, and hinders such movement as donning a coat. Cortisone this time wasn't enough, so she's scheduled for surgery to clean out the scar tissue.

"I had never heard of it, I didn't know what adhesive capsulitis was," Karlitz, of New City, N.Y., says of that first diagnosis. "I would advise anyone with shoulder pain to not wait, and get it checked out immediately."

© 2007 The Associated Press.